Above: Current development along the East River at Pier 36, separate from the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, but shows redevelopment of the waterfront has begun (photo by author)

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy hit New York with devastating effects. The damage cost the city more than $65 million in economic losses. The power was out for about a week after a Con Edison plant, which sits directly on the coast of the city at 14th street, suffered major damages. Flooding in some areas reached up to the second floor of buildings in the Lower East Side. In January 2015, a massive rebuild of the 2.4 mile stretch of the Lower East Side coastal park area was proposed in a plan called the East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) Project. The ESCR plan is a collaborative interagency effort headed by the Department of Design and Construction (DDC) with contributions from the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Parks Department (NYC Parks), and the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency and Recovery. The plan was part of a design competition hosted by Rebuild by Design, an initiative established by the Obama administration to work on coastal resilience after Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast with severe flooding and rain.

Over the past few months, I have done some research about the ESCR as it is something that interests me for its sustainability, resilience, and urban justice implications. I have attended community meetings and talked informally to activists involved in the movement to persuade the city in adopting a more community-oriented plan. I have spoken with representatives from some of the private stakeholders as well as representatives from the DOT and NYC Parks. I have also done research in the Lower East Side on a larger scale, looking at recent neighborhood political issues and leadership. This was what initially led to my interest in the ESCR Project.

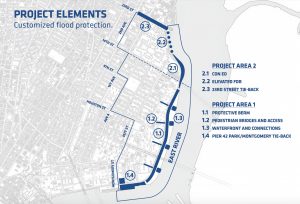

According to the ESCR project’s design, construction will raise the sea wall an additional eight feet. This will supposedly protect the infrastructure along the East River Park from 100-year floods (floods with a one percent probability of occurring in any given year) as well as the predicted sea level rise. Floodgates to close off the FDR drive will also be constructed. These are supposedly necessary since there are areas of highway along the water that aren’t protected by parkland. Overall, the project is meant to serve as a better barrier to the areas of the Lower East Side between 14th Street and Montgomery Street, extending westwards to Avenue B. The federal government awarded the city with $350 million as part of community development block grants for disaster relief, and the city has added its own money to the project, bringing the total budget to over $700 million.

The area that the project is meant to protect is in a Zone 1 hurricane evacuation flood zone, the highest risk in the ranking. This is because the area is close to sea level; wetlands and marshes were there before any built environment. Adjacent to the East River Park is mostly public housing owned by NYCHA. This low-income population is the most vulnerable to flooding, especially those who live on the lower floors. Those living on upper floors with handicap disabilities would be trapped in the event of power outages.

There are a number of advocates for the project that have a variety of visions for what the project should be. City agencies, for example, see this as just part of the natural process of upgrading infrastructure, rather than part of a process of building up coastal resiliency. Of course, De Blasio is an advocate of the plan as his office is heavily involved in its execution. In many cases, New Yorkers have advocated for public parks, community gardens, or other public spaces as an alternative to constructing luxury housing or other kinds of profit-making buildings. In the case of this project however, the debate isn’t necessarily over whether or not the project should proceed, but how it should proceed. The main community concerns include the details about the length and timing of the proposed construction, and what would happen to the community tangentially with real estate development.

Since the entire East River park will have to close during construction, the community will not be able to use the park for a significant period of time. In the first draft of the project proposal, the plan was to start construction in 2017 and continue for five years. Five years is an extremely long amount of time in some perspectives. A parent with a young child, for example, would miss the opportunity to frequent that park and the activity and social interaction would be crucial for the child’s development. The result of this could be many angry parents, but also significant congestion of the other parks and playgrounds in the area, like Tompkins Square Park. Some advocates, especially those part of the East River Alliance, argue that there is an outcome in which the park doesn’t have to close, and instead a barrier could be built over the FDR Drive. This way, the park may get flooded, but the highway would act as a barrier between the park and where the buildings are. This construction would be closer to residents and would potentially require closing FDR Drive. Advocates from the East River Alliance designed this plan and presented it to the project coordinators, but they decided not to go for it, arguing the vegetation in the park would be hurt by the salt water from flooding. To this, an activist in an interview pointed out that the plants that are currently there have survived previous storms, demonstrating their resilience. She accuses the city government of caring more about not closing the FDR than the community.

News reports have noted also that the city seems to be attempting to fast track the project without giving the community a significant time to review the plans and respond. The city was awarded the federal money from the HUD in 2014, and the city must spend that money by 2022. The city had already delayed the project 18 months by March 2018, but the approval for the project was planned for the end of 2018. As of now, the project is planned to start construction in the spring of 2020. Another concern expressed by residents at the meeting was that the project, which had promised to give residents a rejuvenated green space, included a flood wall that appeared to face the city, blocking the community from the waterfront. Essentially the goal of the wall was to protect the city from the water, but this was in response to an environmental need and was not an aesthetic choice that would dissuade people from going. The construction of that wall there would also mean that work would be very close to housing and be disruptive, similar to the plan proposed by the East River Alliance. As The Lo-Down reports, “Trever Holland, chair of the parks committee, voiced similar concerns, saying he’s worried that the flood wall facing the city will be foreboding, as he put it, giving East River Park the feel of a penitentiary.”

Nonetheless, the city took this feedback and addressed some of the concerns. The DDC redesigned the layout of the plans and the wall will now be constructed on the outer edge of the park, closest to the water, rather than the inner edge. It will be hidden underground by raising the average elevation of the park and tapering it off as it gets closer to the FDR, opening it up to the community. The repositioning of the wall was also part of the plan to save time and money.

Of the elected officials that play important roles in the project, City Councilwoman Carlina Rivera is one of the most important, as it is the City Council that will approve the land use. Rivera has been present at many of the town halls regarding the project Representatives from Brad Holyman and Harvey Epstein’s office were also present. Rivera has mentioned that the community does not want to lose the amenities that the park offers, like the barbecue grills that allow for family gatherings. Some have cited the project as being heavily top-down although by looking at past documents and reports, it is clear that project leaders have been working with community members even before the project was proposed. Based on the progression of the project, it seems as if those concerns have continually been addressed. However, Rivera has been quoted saying the intentions for moving the wall closer to the river and reducing the construction time was more for the sake of car drivers and saving money. Over the next few months, there will be continuous meetings and only time will tell how those things play out.

It seems that the long term impact of the project will be somewhat good, in that it will hopefully protect the community from catastrophic storm damage. However, there does seem to be the risk that even in the next 5 years, another Sandy-like storm could hit before the project finishes. It is surprising that the city hasn’t seemed to push this as part of their messaging on shortening construction time. Over time as sea levels rise, are there plans to subsequently adapt for storm surges at that higher level? This seems unclear as of now. NYCHA housing could benefit long term but might still get stiffed in the short term from disruptive construction. A significant concern that doesn’t seem to have been addressed is the possibility of housing prices going up in the neighborhood. Areas around nice parks often experience increased prices, but maybe since public housing is sitting as somewhat of a barrier between the park and market rate housing, it’s possible that it won’t happen. Nonetheless, flood insurance will go down because of lower risks, which also might affect prices. Even though public housing takes up much of the border along the highway, there are still massive luxury developments going up in the area, causing overall neighborhood prices to go up. All in all, housing prices will go up regardless, and we will hopefully see the results of this plan by 2023. Over the next few years, the way that this project plays out will have significant implications for how the city goes about providing sustainable infrastructure to communities. If the community can succeed in its efforts to adopt plans that better fit the needs of the people, this will send a message to the city government and show that the movement to democratize the green city may be successful.

Works Cited

Malone, David. “The East Side Coastal Resiliency Project Will Span 2.5 Miles of Lower Manhattan.” Building Design + Construction, 27 Sept. 2017, www.bdcnetwork.com/east-side-coastal-resiliency-project-will-span-25-miles-lower-manhattan?eid=386053464&bid=1881038.

Litvak, Ed. “City Races For Approval of Lower East Side Storm Barrier By End of 2018.” The Lo-Down: News from the Lower East Side, 29 Mar. 2018, www.thelodownny.com/leslog/2018/03/city-races-for-approval-of-lower-east-side-storm-barrier-by-end-of-2018.html.

The Villager. “Flood of Concerns over E. Side Resiliency Redo.” The Villager, 13 Dec. 2018, thevillager.com/2018/12/13/flood-of-concerns-over-e-side-resiliency-redo/ .

Fuleihan, Dean, et al. “East Side Coastal Resiliency Project: Draft Scope of Work to Prepare a Draft Environmental Impact Statement.” New York City Office of Management and Budget (OMB), 15 Mar. 2015.

New York City Department of Design and Construction, “East Side Coastal Resiliency Preliminary Design Update.” 15 Mar. 2018, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/escr/progress/meetings-workshops.page

Rebuild by Design. “Hurricane Sandy Design Competition.” Rebuild by Design, www.rebuildbydesign.org/our-work/sandy-projects.