In the Humanizing Data working group, thinkers and activists from various disciplines consider the ways that data connects with people, nonhuman animals, and places throughout New York City. Our group aims to address several issues related to data, including what it is and can be, and the ways it has (re)produced systems and experiences of inequality. As the group’s steward, I am excited about the possibilities of arts-oriented public engagements and storytelling as modes to interrogate, communicate, and even advocate for data.

My work on data storytelling began long ago when I was a Graduate Fellow of the University of Pennsylvania’s Program in Environmental Humanities (PPEH), an interdisciplinary group of researchers and students committed to environmental dialogue across disciplines. While I joined this group to work on my own research on the material and visual culture of the ancient world, I was able to use my skills as an art historian in service to collaborative, arts-oriented inquiry that centers public engagement beyond the academy.

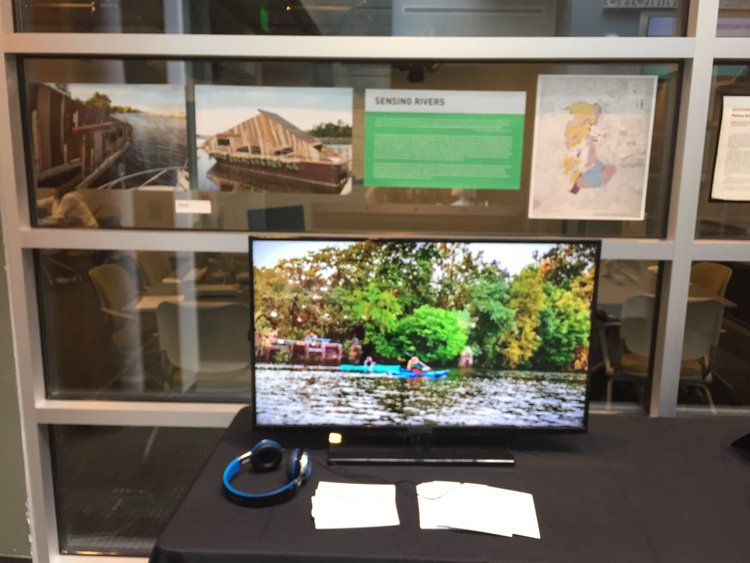

Such engagements began in 2015, when I curated an art meets science installation called Date/um, which was exhibited for public audiences in three locations across Philadelphia. Date/um explored the problem of data, specifically the date, as one kind of datum when creating archives for landscapes, and in this case, Philadelphia’s Lower Schuylkill River. Bringing together artists, scientists, historians, and data librarians, Date/um tackled the challenges that emerge from the incommensurability of various kinds of river data that are used to describe human and nonhuman communities across the Lower Schuylkill River. It was through this installation that I first considered how digital data are grounded in our material worlds, and that data, from its production to its circulation and archival practices, depend on and reflect human intervention. Moreover, the installation highlighted that data, particularly environmental data, not only concerned the scientist, but also thinkers working in the arts and humanities.

These conceptual and epistemological issues came into further relief in late 2016, when a group of students, scholars, and activists organized Data Refuge, which aimed to draw attention to how climate denial endangers federal environmental data. We collaborated to organize over 50 Data Rescue events across North America in 2016 and 2017, where different communities gathered to identify, secure, and distribute copies of federal climate and environmental data so that researchers could continue to access the information. In other words, public, accessible data are vital to a healthy democracy. But we quickly realized that maintaining useful public data required collaboration across sectors and disciplines, which could only be fostered through meaningful conversations facilitated by academics and journalists, activists and artists. By telling the stories of climate data, we can better sustain the lifecycle of data–that is the cycle of its production, storage, security, circulation, and use.

Data Refuge has since grown a public data storybank, which features data stories that connect data to people, non-human species, and places. Such stories have been gathered at various public engagement events, including science festivals, high school and college campuses, and research conferences. And, a new public data storytelling campaign called #MyClimateStory provides new opportunities for online engagement by encouraging people to share how they’re sensing climate change in their local towns. Thanks to support from the National Geographic, Data Refuge organizes a national storytelling project among scholars and activists across five U.S. cities and towns–Philadelphia, New York City, Eugene, OR, Houston, and Baltimore. Each storytelling group focuses on telling local data stories and facilitating public storytelling engagements, which will feature in a May 2020 convening in Philadelphia.

Sensing Data with the (Human) Body

As the Data Refuge storytelling lead here in New York City, I was curious about the other modes by which earthlings communicate and learn information about our worlds. My local climate storytelling journey began by asking, ‘how do our bodies come to sense climate change and also produce climate data?’ From this question emerged Sensing With the Body, a project that centers the data stories and climate experiences of communities in and around New York City, primarily through performance.

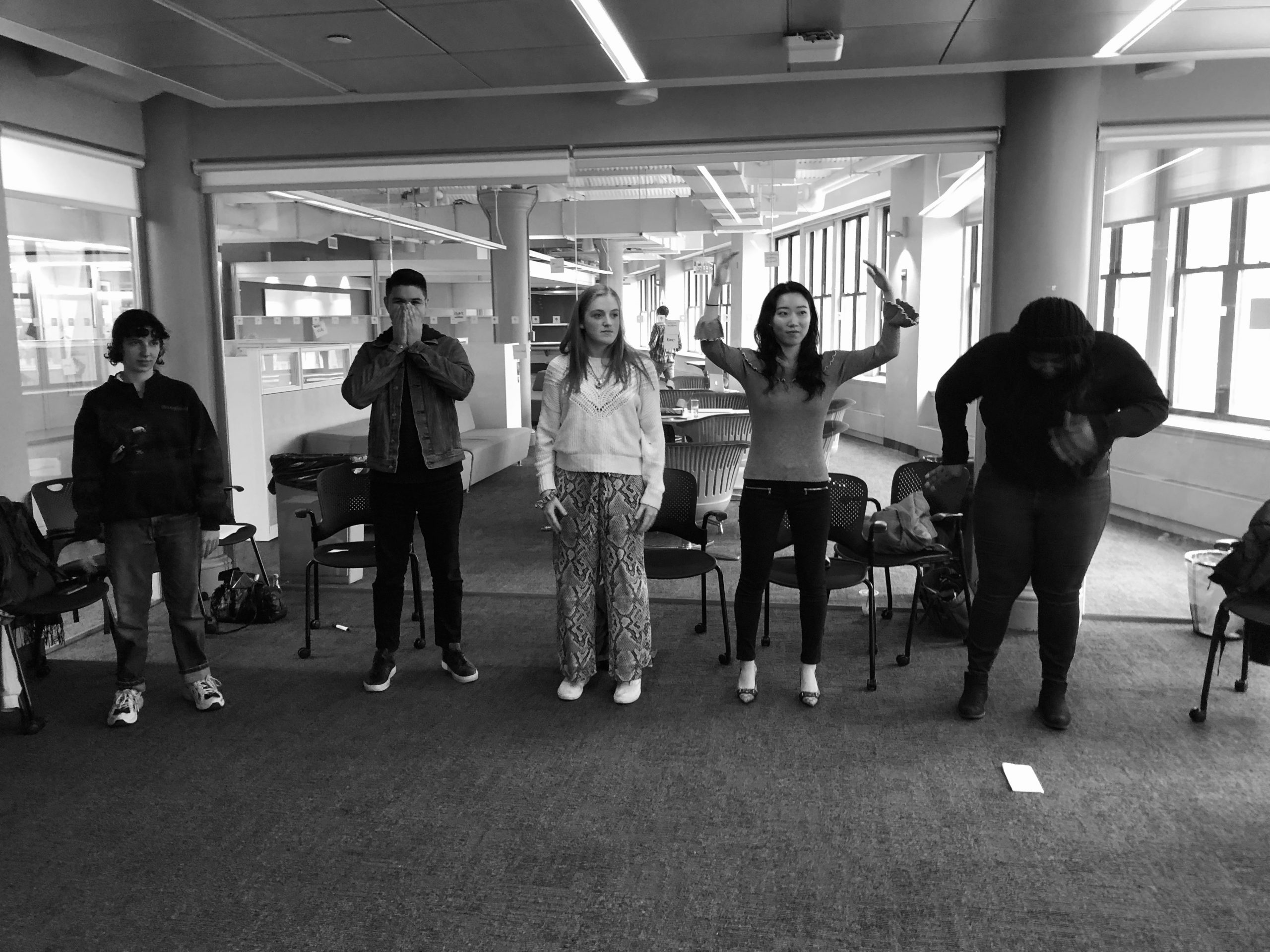

Sensing With the Body consists of interviews with dancers, performers, and scholars of theater, as well as public engagement events that are supported by Data Refuge and the Urban Democracy Lab. With this spirit, the Humanizing Data working group kicked off its first meeting of the calendar year with a public engagement event focusing on Sensing With the Body on February 4th. I co-convened the workshop with Carolyn Hall and Clarinda Mac Low, the duo behind Sunk Shore. Both Carolyn and Clarinda are scientists and dancers by training, and have experience leading groups of people through speculative performances across shorelines that are projected to disappear by 2050. We collaborated to create a series of movement activities for the public workshop.

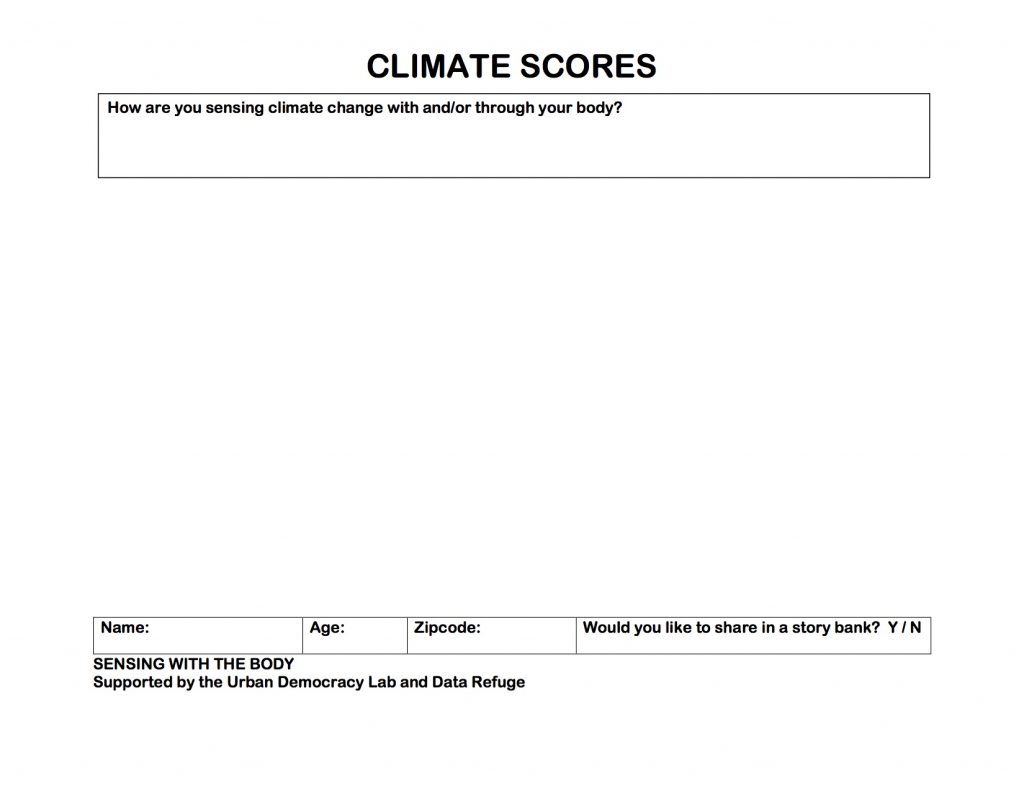

During the workshop, participants came to understand two primary ideas: 1) Objectively reported, measurable climate data connect with and emanate from people and places; 2) Our bodies can be powerful narrative tools that provoke an alternative way of relating to the world, and the quantifiable data that describe it. To communicate these themes, Carolyn, Clarinda, and I co-created and piloted the Climate Score, a new data storytelling tool that guided participants to create a series of movements to guide or loosely script a performance.

Participants first responded to the prompt, “how are you sensing climate change through or with your body.” While each participant responded with individual, personal experiences, they collaborated to co-produce performances that ran 30-60 seconds each. Through bodily movements and gestures, the mini-troupes drew abstract concepts, uncertain futures, and observable events into a realm of comprehension. You can explore some of the climate scores and performances online by following this link here, and contribute your own lived experience of climate change to the growing Data Storybank.

This process of collaborating to create and perform Climate Scores enabled the participants to ‘make oddkin,’ as Donna Haraway might say, “that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all.” (Haraway 2016, 21). Haraway’s concept of making oddkin is critical for navigating our current climate crisis and imagining a future in which multiple species can co-exist. This particular ethical framework might be productive for conceptualizing the premise of data, too. For if environmental and climate justice depends on a collective spirit of de-colonial, feminist, anti-racist, and queer approaches, so too does the production, circulation, and conversations around data.

If you are interested in participating in or presenting your work at the Humanizing Data workshop, sign up here or email pek237 [at] nyu.edu.

Cited Works:

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016)