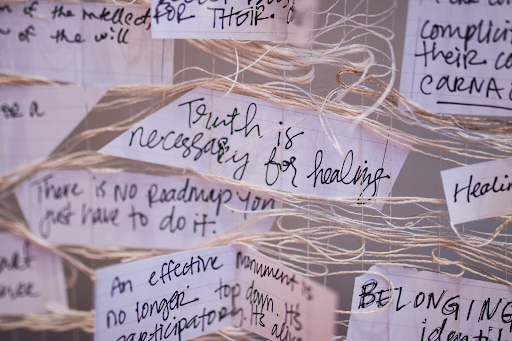

In December, a group of us in the Urban Democracy Lab’s student-alumni Emerging Leaders Program were able to attend this year’s Hindsight conference at City Tech in Downtown Brooklyn. Hindsight is organized annually and is based on a vision developed by the Diversity Committee of the APA New York Metro Chapter to share planning, policy, and community development strategies that work towards more inclusive, just, and equitable communities. This was Hindsight’s third conference and it centered on the themes of erasure, remembrance, and healing. 2019 marks many anniversaries, specifically the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, 100 years since the “Red Summer,” and 400 years since the first Africans to be sold into bondage were brought by European colonists onto occupied Powhatan territory. Those who attended the conference were also called to acknowledge the Indigenous histories that are frequently forgotten and imperfectly remembered. Through the recognition of these histories, and the ways in which they shape spatial politics and planning, the conference highlighted the intersections between community development, collective amnesia, and the possibility of community healing. As attendees, we were challenged to observe which stories are told, which are not, and who is narrating. This resonated with me in particular as a student focusing on power structures in the Anthropocene. I am convinced that building non-hierarchical, accessible, and just communities will lead to more harmonious relationships between humans, other beings, and the planet which we call home. The Hindsight vision for community development furthered my understanding of how to create new, equitable power structures within the current climate crisis.

The conference began with a “fireside chat” in the auditorium of City Tech. The centering of a conversation over fire is a practice that can be found throughout human history and understood as a crucial ritual for community building. This felt like an intentional start to the day. The keynote speakers were Rick Chavolla, April De Simone, Libertad O. Guerra, and Addison Vawters. Rick Chavolla of the Kumeyaay Ipai Nation has been an educator in advancing multiculturalism, social justice, and institutional decolonization, and now works as a consultant strategizing ways to indigenize institutions. April De Simone explores the role of design in activating strategies and outputs within the built environment centered on equity and inclusion. She is the co-founder of Designing the WE, a design firm working toward community-driven social, cultural, and economic development. Libertad O. Guerra focuses on Nuyorican and Latinx social-artistic movements and cultural activism in im/migrant urban settings. She led the community engagement process and study leading to the Loisaida Cultural Plan, an alternative to the city’s 2019 Department of Cultural Affairs plan. Lastly, Addision Vawters works closely with communities to ensure that housing investments are paired with infrastructure and services to promote more equitable, livable places. Addison is a member of Pinko Collective. Specifically, their work explores universal design beyond physical ability, looking at the intersections of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, ability, and design. Each panelist shared their own experiences in cultural work and ideas of how to remain grounded and enthused about the difficult work many of us in the audience are doing.

The conference was split up into five sessions, each offering up to seven simultaneous panel discussions. There were also six exhibits in the lobby and a walking tour of Downtown Brooklyn’s rezoning on offer. After the keynote I attended the “Parcon Resilience” panel, which was led by Andrew Suseno and Kimberly Tate, both developers and teachers of Parcon. Parcon is a movement practice that combines aspects of parkour and contact improvisation. I was unsure of what to expect. On paper, the panel’s focus was described as destabilizing the pedestrian and helping us find ourselves through direct experience with the world. Suseno and Tate started off by asking us to draw or write down what our ideas of “thriving” are. I drew a haphazard setting of Earthaven, the intentional community where I had spent the summer of 2019. I drew children running barefoot, people singing, others skinny dipping in the creek, and a lot of greenery, sunshine, and animals. After we had all drawn our own idea of thriving, we gathered in a circle, and Andrew led us through a thought exercise of what it means to undo the pedestrian. By this, he meant: how can we get in touch with our surroundings, embrace play, and make our environments suit our needs rather than us conforming to the needs of the dominant culture? We started to deconstruct the pedestrian model of sitting in a chair. All of us, sitting respectfully with our backs straight and legs crossed or close together then began to experiment with different forms of sitting. Some flipped over their chairs, others sat backwards and straddled their backrests. Some laid down on their bellies. We continued to play, and continued to break down the societal constructs of how we are supposed to sit in a chair. Andrew continued to lead us into new exercises. The chair was always included, but we were encouraged to explore the other parts of the room. Folks stood on tables, stretched their legs over hand rails, and hung upside down over the glass barrier. I felt incredibly free. The ability to safely move my body in a way that felt good to me and did not interfere with anyone else’s play, made me question why I don’t embrace this flow in my day-to-day life. Or rather, why doesn’t anyone? The experience made me realize that all of the play that I had found at Earthaven quickly diminished upon my return to New York City. It is a city designed for pedestrians, and as per Andrew and Kimberly’s vision, we should start designing spaces that induce play, rather than maintain controlled pedestrian activity.

For session two, I chose to attend “Decolonizing Practice: Design Justice as Self-Determination.” Chris Daemmrich—facilitator of design and collaboration for racial, gender, and economic justice—led this session and described effective ways of deconstructing the ways in which design has been used as a means of White supremacist, cisheteropatriarchal, capitalist domination. What might “design as the practice of freedom” look like? Seated at large tables, Chris led the group through a series of practices, first asking us to describe a place that shaped our childhood, then having us describe people we admire, communities to which we belong, and values we associate with those communities. With these critical questions in mind, we opened up discussion and collectively described our ideals and how our histories have helped or hindered how we can achieve a just future.

The last two panels I attended were on a similar wavelength: “Digital X Physical Queer Spaces: Data, Equity, Memory” and “Transgender/Gender Nonconforming Professional Communities: Talking Future!” I was drawn to these sessions because I believe that, through an understanding of LGBTQIA+ histories and current movements, we are better able to understand and plan for more just futures. In the “Digital X Physical Queer Spaces” session, we talked about the presence of digital and physical queer spaces (e.g. Grindr and the gay bar) and their accessbility, openess, and existence. The discussion centered around the making of a “Queer Digital Utopia” and data such as sexuality, number of partnerships, and gender identity that is needed to create these spaces. How to obtain this data is one of the biggest roadblocks in creating equitable spaces for already marginalized populations. The group split into small discussion groups to discuss topics from “gayborhoods”—geographical areas inhabited or frequented by the queer community—to sex workers’ online presence. We reconvened, were given a number to which we could text our ideas, and started individually sending our thoughts on what queer digital spaces meant to us. Our words and phrases immediately popped up on a screen in front of the room so we could consider the kinds of key discussions that were being had throughout the room. The experience was one of collective cooperation and it was promising to be in a space with like-minded strangers, all advocating for the planning of spaces that are accessible to all.

Attending the Hindsight 2019 conference was an incredible learning experience for me. As I was led through stories and memories of different marginalized groups, different movements, and other people’s histories, I was moved to remember specific moments in my life that shifted the way I see the world around me and helped me critique or expand my knowledge base. It is through the sharing of stories that we are able to connect with each other on the deepest of levels, and I believe Hindsight allowed ample space for that kind of connection. I left the conference with an enthusiasm for play as a mode of interacting with urban space, a growing appreciation for listening to others’ stories and telling mine, and much curiosity about how to build inclusive spaces on the ground, between one another, and in the digital world. Hindsight challenged, broadened, and confirmed my optimism about building communities as a foundation that will both work as and further create solutions in the Anthropocene.