The “Right to the City,” a term first coined by radical geographer Henri Lefebvre in 1968, has become a popular organizing principle with contemporary urban activist groups and movements. The Right to the City describes a certain praxis of urban citizenship that explicitly attempts to dismantle capitalist commodification of the city. Lefebvre argues that the working class must demand a “transformed and renewed right to urban life.” David Harvey, a contemporary Marxist geographer, adds new meaning to the term by claiming that the Right to the City is “far more than a right of individual access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart’s desire.” I seek to apply this concept to an entirely new context: urban China. With vibrant public life, an explicitly socialist past, and a completely unique urbanization process, China presents numerous intriguing points of entry to examining the Right to the City outside of the West. My analysis of the Chinese case, based on fieldwork conducted in Shanghai and Beijing, reveals that Chinese people’s perceptions of public space do not align with an orthodox understanding of the Lefebvrean or Harveyan Right to the City. Instead, there is an equally crucial, inexplicitly political, and pragmatic relationship to public space, forged from China’s unique political history and process of urbanization.

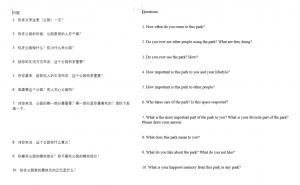

My research in China consisted of 6 interviews in Shanghai and 6 interviews in Beijing over the course of 2 months. These interviews were semi-structured and involved written answers from participants along with casual conversation and participant observation. Each park I visited to conduct interviews had a unique character due to scale, context, or design. I attempted to vary these sites in order to provide a broad picture of the city’s public space as a whole. I attempted to interview a similarly diverse array of participants to further this goal. From these interviews, I translated and compared individuals’ responses under the analytical framework of the Right to the City.

My research not only examined people’s opinions and memories, but also cross-referenced their responses against my own analysis of the built environment. I was most interested in contextualizing the contemporary Chinese city as a product of the past hundred years of intense change and development. The central theme of scholarly work on this topic is the idea of walls to window dressings. Succinctly, the pre-revolutionary Chinese city was one defined by enclosure. Restriction of the flow of peoples and control over who might access or view different parts of the city was a key planning value. This organization scheme transcended class—with the rich living behind massive walled structures and the poor living in densely packed, contained neighborhoods. After 1949, the Maoist revolutionaries took on the task of urban planning and reorganization with strictly materialist principles as their guide. The belief that the built environment could imbue society with new values and promote collectivity in economic and cultural spheres lay at the crux of the Communists’ beliefs. Therefore, many of these walls were torn down and old structures were cleared to provide gathering space for large groups of people to rally and participate in revolutionary activities. Finally, after the Reform and Opening Up (1976), the policy of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics led to unforeseen rates of urbanization and development, as well as the cultivation of a new urban aesthetic which transformed the huge public spaces opened up by the Maoists into picturesque “window dressings” for the new corporate skyline of booming cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen. These sites have been critiqued by urban studies scholars and geographers for their lack of functionality and performative nature. The “insensible location and design” of these publics “alienate common people further with their estranged relationship to the surrounding city.”

It is within these three conflicting ideologies and histories that contemporary Chinese cities are experienced. Parks that I visited contained certain elements left over from each phase. I intentionally chose sites that fell in between the extremes of the aforementioned ideologies. It was in these spaces, I predicted, the Right to the City might be found.

An abundance of data from the surveys showed that people in parks frequently transform public space in order to meet their basic needs. Many of these instances involved spontaneous organization and appropriation of government owned public space as a response to macro issues such as pollution, public space shortage, or care for the elderly that the government failed to adequately address. Importantly, all of these events occurred in a quotidian, pragmatic fashion. A close reading of the politics of Chinese citizens’ attitudes and interactions with public space, however, can tell us more about hidden ideological work of the built environment, as well as the latent revolutionary potential within a community.

An example of this can be found in the numerous dance groups that occupy parks, squares, shopping centers, and avenues in most major Chinese cities. These groups are mostly made up of ayi, or “aunties,” who meet after work or dinner to dance. Different groups practice different styles of dance ranging from square dancing to ballroom to traditional Chinese dance. They are rigorously self-organized—arriving at the same time every day, sometimes even wearing uniforms or matching colors. The groups of ayi come out in such impressive numbers that sometimes you can barely navigate in between their routines. Each group stakes out their own portion of space to perform, clearing movable furniture like benches or bicycles. They sometimes even set up makeshift coat racks for their group members to hang their belongings before they begin. With a portable speaker blasting their setlist, competing with other groups’ speakers for airwaves, they begin to dance. This can go on for hours, and the ayi, despite their age, never seem to tire.

The ayi’s transformation of public space is twofold. First, they change the space from its intended function in order to support their recreational activity. Second, they transform the relationships of urban dwellers from passersby to participants and observers. The physical altering of public space is only one part of the story. Community organizations like dance groups alter the idea and meaning of space. Large open spaces or wide streets were once constructed for political and revolutionary purposes. Now, they help community members socialize and escape the intense pressures of contemporary Chinese society. Many respondents expressed the idea that parks were some of the only spaces they could release pressure or relieve mental stress. In a country of over 1.4 billion, intense competition and pressure accompany people of all ages. Ayi’s are frequently hidden from public life but are just as affected, burdened by unglamorous tasks such as cooking or child rearing. In these newly created spaces, they become visible as part of a collective. They demand prominence and acknowledgement through the power of performance. Individuals who walk by or occupy other areas of the park are now engaged as audience members, offering their existence and attention to the ayi in exchange for entertainment. A woman I interviewed in a Shanghai park praised the dance group performing nearby, adding that it made her happy to see and hear such activity. As I collected data from others, the sounds of drums and dance music became the background noise for my experience of researching parks.

These spaces, transformed from political staging grounds to informal dance stages, stimulated interpersonal connection through performance rather than political identity in a new and important way. It is clear that Chinese citizens endeavored to remake certain urban sites in order to better reflect and serve their needs and desires. But is this demonstrative of a Right to the City? I don’t think so. The Right to the City suggests a conscious form of class struggle to remake the city according to a certain ideology. The perceptions of space that I analyzed from my interviews indicate that the actions taken by Chinese citizens to remake their city are pragmatic ones, not consciously political ones. While political themes are brought up in individuals’ responses, there is no evidence of political organization around the issues discussed like the environment, the economy, or gentrification. That’s not to say that the public spaces and public activities I observed do not exhibit their own brand of inadvertent political meaning. The altering of space in a bottom-up direction challenges the overarching narratives of Chinese urban development as a government-driven success. Further, the subjects and objects of this informal urban transformation highlight the priorities and aspirations of the Chinese urban population as they work to remake their city into one closer to their hearts’ desire. A more conscious political mobilization around urban issues could allow citizens to demand more control over the powerful tools of urbanization and development the central government holds. In many ways, the Chinese city has been in constant revolution (though of different sorts) over the past hundred years. If we follow Harvey’s thinking, a conscious Right to the City movement in China could open up new opportunities for citizens to engage more meaningfully with their recent revolutionary past as well as develop a new praxis of urban citizenship that addresses the currently needs of the individual and the community within a mass society.

Therefore, I think it is necessary to acknowledge the Chinese case as an important one, full of latent revolutionary potential. The built environment, informed by an explicitly socialist past, supports an urban social life that exercises a specific transformative and organizational power. From this elaborate context, we can imagine the vast potentialities of a Chinese urban movement intent on remaking the city to better remake the self. That’s not to say that the Chinese people ought to strictly work towards achieving a Western model of urban social praxis, but certainly that the Right to the City provides an interesting and important framework to analyze the Chinese cities of today.

Bibliography

Gaubatz, Piper. “New Public Space in Urban China.” China Perspectives, 2008, 72–83.

Harvey, David. “The Right to the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27, no. 4 (December 1, 2003): 939–41.

King, Loren. “Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City.” In Philosophy of the City Handbook, edited by Sharon Meagher and Joe Biehl. Routledge, 2018.

Lefebvre, Henri. Writings on Cities. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell, 1996.

Low, Setha M., and Neil Smith, eds. The Politics of Public Space. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Lu, Duanfang. Remaking Chinese Urban Form: Modernity, Scarcity, and Space, 1949-2005, 2005.

Miao, Pu. “Brave New City: Three Problems in Chinese Urban Public Space since the 1980s.” Journal of Urban Design 16, no. 2 (May 1, 2011): 179–207.

Wolch, Jennifer R., Jason Byrne, and Joshua P. Newell. “Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough.’” Landscape and Urban Planning 125 (May 2014): 234–44.