Based on research conducted in Cape Town, South Africa throughout July and August 2016, under institutional support from NYU Africa House

Central to Jewish ethics is the age-old adage, “love thy neighbor.” Religious leader Hillel is said to have described this as “the whole of the Torah,” even calling the rest “commentary.” But in Sea Point—an affluent and densely-populated suburb of Cape Town, South Africa—the phrase took on new meaning last spring, when called upon during a land battle which unfolded between parents advocating for a Jewish day school and activists campaigning for public housing development. Since dubbed the Tafelberg Saga, the dispute has come to exemplify the necessity for innovative approaches to race, space, and distribution in Cape Town. Almost 3 decades post-apartheid, supposedly-integrative policy has done little for the city’s native African population—much of which still dwells in slums spotting the periphery of a bustling city bowl.

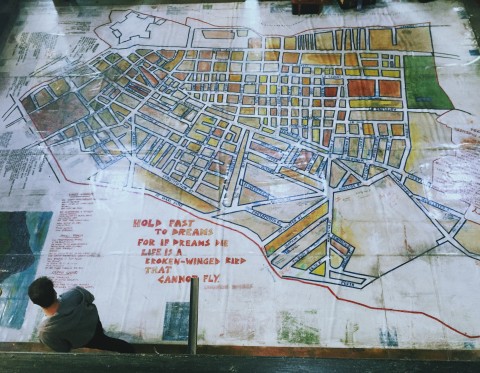

It is difficult to convey just how starkly “difference” rings throughout urban South Africa. The spatial engineering of apartheid is blatantly ingrained within Cape Town’s plan: according to the African Center for Cities, townships and informal settlement areas remain racially-homogenous and vulnerable to fires, floods, crime, violence, and eviction, while wealthy neighborhoods and gated communities surround business districts rife with economic opportunity. Beyond issues of profound segregation, the South African Civil Society Information Service notes that 400,000 families of color do not have access to basic services and shelter in Cape Town; the city’s housing backlog is estimated to grow at a rate of 16 to 18 thousand units per year. Meanwhile, in what might rightfully be called “the other Cape Town,” cozy communities like Sea Point have become freckled with pressed juicers and espresso bars.

Guy Briggs, Head of Urban Design at dhk Architects, said that the foremost reason for these modern inequities is that apartheid policies were “hugely successful” in executing what they intended. “Planning and implementing segregation is essentially a violent act, and violence is easy,” he noted. “It’s far more difficult to make peace and to stay at peace and to live at peace and to have solutions that continue to work.”

Of all the policies codified under apartheid, those targeting land distribution have certainly proven the most devastating to modern racial dynamics. The 1913 Black Land Act prohibited black South Africans from owning or renting land outside reserves relegated to a mere 7% of the country—designating 93% of land to the white minority. The 1923 Urban Areas Act then permitted forcible removal of black South Africans living on the outskirts of white industrial areas, and the 1950 Group Areas Act made residential segregation compulsory. Although the regime fell in 1991, very little has changed for Cape Town’s demographic geography. Briggs said that the distribution of people by race is almost exactly as it was 20 years ago, and that the distribution of people by educational attainment or income level is as well.

Within this framework emerged the Tafelberg Saga, premised on an affidavit by Thozama Adonisi, a domestic worker employed in a predominately white, Jewish Sea Point neighborhood. Her story embodies somewhat of a universal for many current or former township-dwellers who either make excessively long, dangerous commutes into the city for work, or endure housing abuse in below-standard quarters to stay employed. Adonisi grew up in a home of 12 in the Gugulethu township. In 1998 she rented a small flat in Sea Point with seven other people, but was evicted by men in plainclothes—with no court order—when the person she sublet from failed to pay their landlord. With help, she then found a maids quarter where she shared a single shower with 15 others, but fought to stay in because its address meant good school access for her daughter.

Adonisi remembers being told as early as 2010 that the site of the old Tafelberg School, located on a plot of land for sale in central Sea Point, had been earmarked by the government for social housing. This was precisely the case: a 2012 feasibility study prepared for the Social Housing Regulatory Authority concluded that “the Tafelberg School property is very well suited to residential uses in general, and social housing in particular as its primary land use, and will likely provide the only social housing opportunity on the western seaboard side of the Cape Town City Centre.” As such, The Saga emerged when parents at the Phyllis Jowell Jewish Day School—located in opulent Camps Bay—began to advocate for its relocation to the Tafelberg site. To additionally complicate matters, controversy unfolded around the vested interests of legislative officials who own property near the site, raising questions of whether stakeholders at the state level would fight more for social good or private profit.

Activists and workers like Adonisi were outraged, arguing that building a private school in an already-wealthy community would be futile to integration efforts—and a significantly devastating loss, given the capacity of the site. After all, affordable housing in the right locations has been identified by the McKinsey Global Institute to boost productivity by integrating lower-income populations into the economy and reducing costs to provide shelter and services. One report asserts that “it enables labor mobility, opening a path to rising incomes, giving households more to spend on goods and service in their neighborhoods and, over time, enabling them to move up the income pyramid and help drive the city.” After months of campaigning on this premise, legal activists from the local group Ndifuna Ukwazi actually succeeded in halting the sale of Tafelberg to Phyllis Jowell. In November, provincial government requested a new feasibility model for social housing on the site, which showed that 270 affordable rental units would be possible. The model contributed to a public participation period which aimed to assist the Province in deciding whether or not to continue with the original sale—its comment period just closed on February 15.

Whether or not Ndifuna Ukwazi actors succeed in securing the plot for public good, Tafelberg is still just one small plot of land in which these ideals became contested. However, its story becomes important when considering the precedent necessary for Cape Town to move forward with innovative, integrative efforts in mind. A Future Cape Town piece on The Saga asserts that “occupying land is a direct response to the housing crisis” and that “equitable spatial integration and sustainable settlement upgrading in city spaces can be prioritized as viable responses to the urban land question.” Widespread calls for radical policy upheaval must, therefore, be matched by radical implementation efforts—much of which will come not from the state level but from developments on small-scale city blocks, built to bring together mixed-income neighbors willing to practice what they preach.