Professor Louise Harpman introduced “Dadaab is a Place on Earth” by saying: “Gallatin is a place where we ask questions that have no answers.” This week’s events did just this: asked questions not easily answerable about society, humanitarianism, displacement, home, urbanism, empire, and the built environment. Throughout Monday night’s event, Dadaab—a place that international media outlets have called “the largest refugee camp in the world”—as a city, a place, a prison, a “warehouse,” an encampment in the margins, was constructed before our eyes through the words of Anooradha Siddiqi, Alishine Osman, Ben Rawlence, and Samar al-Bulushi, the four distinguished panelists. Each of the panelists provided their own perspective on the refugee camp, lending insight into the architecture, politics, and economies of Dadaab.

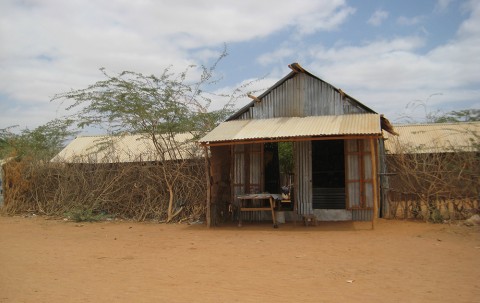

“Dadaab is a Place on Earth” was part of African Cities Week, April 17-21, a week of events that was cosponsored by the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, the Collaborative on Global Urbanism, the Robert L. Bernstein Institute for Human Rights, Global Design NYU, Institute for Public Knowledge and Race and Public Space Working Group, the NYU Center for the Humanities, NYU African Studies, Metropolitan Studies, and NYU’s departments of English, History, Art History, Social and Cultural Analysis, and Sociology. Much of the Monday night event was spent deconstructing the narratives surrounding the camp specifically, and the migration crisis in general. “We must remind ourselves,” said Professor Anooradha Siddiqi in her opening remarks, “that the narrative of the migration crisis as a recent phenomenon is a Eurocentric narrative which often excludes African concerns.” For that reason, looking at the architecture of Dadaab is a way of understanding the camp as an actual built material, an object with a longstanding history, rather than part of some kind of Eurocentric crisis. Crisis, Professor Siddiqi reminded us, implies temporariness. Yet Dadaab, Kenya was founded in 1991 during the Somali civil war, and for the past twenty-six years has seen many children raised inside the camp, houses built, and families expanded, growing to Kenya’s fourth largest city. Ben Rawlence, author of City of Thorns, offered a striking image that symbolized the growth and duration of the camp’s existence: Thorn bushes that Somali refugees had planted when they first arrived at the camp have now grown, over the course of more than twenty-five years, to three meters tall. Alishine Osman, a panelist who lived in Dadaab for much of his life, pointed to how the architecture of the camp has changed alongside the thorn bushes. At the beginning, the UN built a couple houses. Then, tents filled with families soon joined them. Small houses were later built, with bigger houses appearing later on. Time passing, shown through plant growth and progression of architecture, also raises questions about UN and government policies for people who have been displaced. Long-term encampment as a United Nations’ policy for displaced peoples is a relatively recent development, and Mr. Rawlence pointed out that extended encampment is actually against a United Nations charter. Professor Siddiqi drew significant parallels between the United Nations’ humanitarian policies and the colonial enterprise, an extension of the colonial nation-state as a territorial project. Humanitarianism, she warned, is not politically neutral.

Situated literally and figuratively in the margins of Kenya, the construction of the camp along the northern frontier was not only a signal of the Kenyan government’s willingness to host Somali refugees, but also revealed a desire to keep them at arm’s length, connecting with a long history in the region of enforced “villageization” schemes and detention camps for ethnically Somali nomads. When Dadaab was founded in 1991 as Somali refugees fled Somalia’s civil war, it was planned for 90,000 people. Its population has since grown, as conflict in Somalia rages on, to a staggering half million people. In a world reliant on the nation-state as an organizing mechanism, what happens when half a million people are suspended somewhere along the citizenship spectrum? Is Dadaab a temporary stop along the way or a destination? What is the future—what is the endgame? How long do people need to live in this place to no longer be considered “displaced”?

Is Dadaab a city? This is one of the many questions that came up during the question and answer session; how do we define city—is it a question of population size? Or of city dwellers’ imagined futures? While Dadaab might share similarities with cities like New York or Nairobi—Alishine Osman mentioned its large and diverse economy, roads, police, schools, and TV’s as its key urban characteristics—it also has important differences. Namely, the inhabitants of Dadaab can’t leave; their mobility is restricted by the Kenyan state. Police checkpoints along the roads leading away from Dadaab ensure that the refugees in Dadaab stay in. In this way, Dadaab imitates a prison, working as a “carceral city.” The United Nations’ plans for the camp elaborate upon this theme: the roads and districts are planned with a panoptical effect; the straight lines and methods of resource distribution among the districts serve as a sort of strategy for control observation, a rigid form of surveillance. These architectural strategies are mirrored in the Kenyan government’s policies toward Dadaab as whole, as Samar al-Bulushi pointed out. As the Kenyan government increasingly takes on the narratives of the War on Terror, Ms. al-Bulushi explained, rescaling the threat of terrorism as a real and present danger in Kenya, Dadaab has become re-imagined as a problem space, where terrorists and al-Shabab recruits lurk. By locating the terrorist threat in Dadaab, the Kenyan government justifies its close monitoring of the population and restriction of movement, even threatening to close Dadaab for fear of terrorist activity simmering among the camp dwellers.

Despite these restrictions, the thorn bushes planted over twenty years ago grow over and overwhelm the strict lines and planned avenues of UNHCR, contributing a feeling of informality to the urban landscape and reorganizing the urban space. In many ways, the inhabitants of Dadaab claim the city as their own, interacting through informal economies and means. At the end of the panel, Ben Rawlence shared an anecdote of an interaction he had had with a young boy he knew in Dadaab who was returning to the camp: “I feel like I’m returning home,” the boy said to him. In spite of the restrictions and regulations put in place in Dadaab, in spite of a situation that might seem hopeless, Dadaab, for many, has become a home.